Publishing a gut-spilling memoir certainly clarifies what it means to act with intention. This is not language I’m entirely comfortable using. Despite the fact that I’ve lived in Northern California for sixteen years, I have yet to read a book by Deepak Chopra, who wrote, “Your focused intentions set the infinite organizing power of the universe in motion.” Chopra believes the universe has bigger things in store for us than our blinkered brains can imagine, different outcomes than the ones we try to force.

I’m here today to say that the man knows whereof he speaks. The unforced outcome of your dogged intent, the thing that shows up out of the blue, that you never saw coming, that you couldn’t have dreamed if you tried—that thing the universe has up its sleeve for you is stupefyingly amazing!

I’ve written elsewhere about some of the uncanny connections my book has allowed me to make with some wonderful people. I told myself those were very cool coincidences, nothing more. My apologies to the universe for not recognizing your handiwork right off the bat.

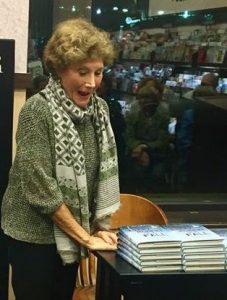

In May, after the reading I gave at my local bookstore from Every Moment of a Fall: A Memoir of Recovery Through EMDR Therapy, people lined up to have their copies signed. One woman seemed to hesitate when her turn came. I said hello. She kind of stammered how much she enjoyed the reading. There was a pause. Then she told me her name was Carol, and that she grew up in Concord, Massachusetts, where I’m from, and where the plane my dad was flying crashed when I was sixteen. Then she said my sister Nancy, who was killed in the crash, had been one of her closest childhood friends. They’d spent summers together at the Concord Country Club. Then she told me she lives right here in the same small California town as me. Then she said she’s a psychotherapist. Who does EMDR.

Mind fully and completely blown, courtesy of the universe.

I couldn’t really make words come out of my mouth. I was in the middle of signing her book and found myself writing, Wow! Wow! Wow! Somehow, I had the presence of mind to hand her a Post-It note and ask for her email address. It took me a couple of days to convince myself that the unfathomable had actually happened. Then I emailed her.

We went for the first of what would become many walks. We established that Carol and my sister Nancy were the same age, four years younger than me. Both Carols (she and I) have a sister named Sue who is four years older than we are. Which makes Carol’s sister Sue my age. It slowly dawned on me that we were in the same high school class. We played freshman field hockey together.

Carol and Nancy became friends because they both felt ostracized by the other kids who spent their days at the club pool. This is not hard to imagine. The country club was home territory to the New England uber-WASP. So Nancy and Carol kept to themselves. Carol described a little stand of apple trees between the pool and the tennis courts where they hung out, eating lunch in the shade. Maybe once or twice chucking apples at passing cars. And talking for hours about all kinds of things, like what they struggled with or longed for in their twelve-year-old hearts. For years after Nancy died, Carol felt like she’d never find another friend who got her the way Nancy did.

This was my bratty little sister we were talking about. The one who couldn’t let me be for five seconds without dropping the cat onto my book, or snapping off the bathroom light from the outside, or tattling to Mom that I’d used my allowance to buy candy. I’d never given any thought to the possibility that she’d had an inner life, that she harbored secrets and dreams she’d never shared with me. Suddenly, here was a person who admired my sister in a way I never had, giving me a glimpse of the textured creature I never knew her to be.

I tried to convey how meaningful it was to learn these things about Nancy all these decades later—to get a peek into my sister’s psyche. And how great it was to hear about Carol’s own life—her time in college and grad school, her husband and two kids, the places she’s lived and the work she’s done. Not only was it lovely to start to know Carol, getting acquainted helped me picture what Nancy’s life could have been like had she survived.

We hugged goodbye and Carol offered to be my adopted little sister.

After that first walk, I dreamed about Nancy. She was a small child in the dream, while my sister Sue and I were our adult selves. We were protecting Nancy from a bully, using our grown bodies to shield her. Another woman in the room with us began urging me to let Nancy fend for herself, warning me that was the only way my little sister would learn to roll with life’s punches. I became enraged, shouting at the woman to butt out, telling her she had no idea what a troubling past Nancy had endured.

When I woke up, I wondered if the other person in that room was me too, in the way it sometimes goes in dreams, where we play multiple characters and see the action from multiple perspectives. Maybe my dream was showing me two sides of the coin, two versions of the story of Nancy’s life. The version I’d vehemently guarded for years cast my sister as a helpless child. Now that was being challenged by critical new information, by all there was to learn about my sister from a second Carol, who remembers Nancy as capable, even fierce.

After that first walk, Carol had a similar experience. She made a painting about Nancy. It turns out that, in addition to being an EMDR therapist, Carol has an MFA in painting. It’s her vehicle for addressing and processing complex emotions, or working through knotty problems. Meeting me, reading my book, learning things about her friend she’d never known before had unsettled her. She began to think she had idealized Nancy in some ways, making her stand for certain Big Important Things in her mind. So she made a painting to work through that. The one at the top of this page.

When Carol first showed me the canvas, all I could think was: coast of Maine. That’s where our family spent much of my childhood. But beyond the immediate personal association, there was something starkly elemental about the work, its juxtaposition of a cold, stony (one might say frozen) bluescape against the warm browns, ochres and greens of the overlaid trees Carol collaged in. Those greens and yellows are slowly seeping into the blues, as if the two versions of Nancy’s story, slapped together, are merging. Making something new.

Perhaps it’s impossible to keep ourselves from freezing the dead in past time, or idealizing them as we begin to forget the subtler things. I think both of us Carols allowed Nancy to become more of a symbol of something we needed to believe and less of a person, as time passed.

Today, thanks to the improbable ways of the universe, I’m getting a peek at the real girl who sat under those apple trees sharing her struggles. I acted with intention, releasing my story into the world, and the outcome is something I never could have imagined. I’ve been given the chance to understand that my little sister may have only lived twelve years, but she had a robust emotional life, and a kindred-spirit confidante. One who answers to my name. One who I now call sister and friend.